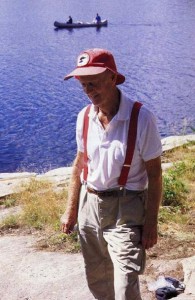

Some people go into Quetico to fish, some to find solitude and others for the scenery and wildlife. Others, however, like Charles “Chuck” Farnum and his extended family, are “bush-whackers” extraordinaire; they seek out and explore places that are seldom visited. If Chuck Farnum, the clan elder, wouldn’t have been become a doctor, he would have been a terrific wilderness guide or explorer. A modest man, he simply describes himself as “primarily a traveller that likes to investigate out-of-the-way places.”

Jim Clark and Bud Dickson, who with their their wives are co-owners of Canoe Canad agree that in twenty-six years of outfitting canoe trips the Farnums “are definitely most adventurous trippers we’ve ever encountered”. From Jim, I first heard about Chuck Farnum’s off-trail exploits and I was fortunate to have encountered the Farnums this summer on a cool, bright August morning in the Pickerel Narrows. Three generations of Farnums, spouses and offspring were heading into Quetico sixty-two years after Chuck Farnum’s first Quetico trip.

His first canoe trip was in 1929 while attending Camp Minne Wanka in Three Lakes, Wisconsin and his first trip in Quetico was in 1937 after he had heard glowing accounts of it from a doctor friend. For his first few years, he obtained some items and advice on canoe routes from Border Lakes Outfitting in Winton, Minnesota, which was then run by Sigurd Olson. He then paddled north into Quetico and Chuck Farnums canoe trips have continued to the present.

1944 was a pivotal year in Chuck Farnum’s life: he got married, obtained his medical degree from Northwestern University, took a canoe trip into Quetico with his wife, Betty Farnum, and entered the U. S. Army. He was discharged from the Army in 1947 and settled in Peoria, Illinois where he specialized in internal medicine until his retirement in 1985.

Chuck and Betty had four children and, in the years when the children were growing up, Betty and her daughter visited her mother at a cabin in the Muskokas in southern Ontario when Chuck went into Quetico with their sons. During the years when their three boys were small, they came into Quetico from the north and used Indian guides. Chuck has especially fond memories of Harry Bombay, a trapper and guide from the Atikokan area who “was wonderful with the boys and became our true friend”. Like many doctors, Chuck Farnum was on call 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Betty Farnum said that during these busy and stressful years “thank goodness, he had canoe trips to restore his soul.”

Since those trips with his three sons, many different colleagues, friends and family members have accompanied the Farnums on their journeys. The family has grown over time by marriages and the arrival of grandchildren. Tragically, the family was diminished by the death of two of the sons in the last few years. When talking to Chuck Farnum about the places he’s visited in Quetico, I become painfully aware of the number of times that I considered going up some shallow, overgrown creek or getting out the compass and heading cross-country to a small lake but decided against it. Sometimes I did venture out and was rewarded with the experience of visiting new places, but too often I thought “maybe next time” and stuck to the easier, more established routes.

While many have only contemplated paddling north of the Maligne River up Wildgoose Creek or Trail Creek, or exploring the areas east of Agnes Lake by heading up Dettburn Creek, the Farnums have travelled these creeks and many more. Creeks in the boundary waters area are usually brushy and require numerous pull-overs, duck-unders and the strong possibility of dragging the canoe while slogging in muck. Patience, innovation and a willingness (or better yet, an eagerness) to get wet, dirty, bug-bitten, scratched-up, tired and sore are the keys to successfully negotiating these creeks. Small creeks almost inevitably originate in small lakes and frequently in small lakes that are seldom visited. From these lakes, the Farnums reason, other lakes can be reached by simply taking out a compass and heading cross-country.

Guides working in the Boundary Waters in the 1920’s and 1930’s used maps that were rudimentary and incomplete. These maps, lacking the detail of contemporary maps, didn’t show many of the smaller lakes and creeks. Thus, visitors and their guides consequently were more adventurous in seeking out new places to explore and fish, and frequently went up creeks and over ridges not knowing what they would find on the other side. Atikokan guides like Harry Bombay, Phil Sawdo, Richard Tennesco, and Lewis Tennesco frequently sought out new places to fish and took willing customers with them. Sigurd Olson, who learned from similar guides in Winton and Ely, described this type of exploration in his book Open Horizons “When I was not too sure what lay ahead, I would leave the canoe and head for some distant hill to climb a tree and look for a spot of blue. Some times the men would come with me, enjoy the adventure as much as I. Once we saw the blue we returned to the canoes, then with saws and axes we cut the trail. Those portages were often long and rugged, and frequently they led to little lakes that had no outlets or connections with waters beyond, but with the excitement of standing on a shore none of us had seen before more than made up for the backbreaking labor of getting there”.

Chuck Farnum paddled with, talked to, and learned from some of these guides on his earlier trips. He obviously never forgot the joy of seeking out new places and later discovered the joy of passing these skills on to others. Chuck, his son Jim, daughter Patty, spouses, grandchildren and friends continue the quest of explore Quetico’s hidden places.

One of their journeys was up Devine Creek, which flows into the east side of the south end of Kawnipi Lake. Like many others, I have started heading up this creek but turned around when it got shallow and progress became difficult. It is always easy to decide to wait until the water is higher (although it will never get high enough to make it an easy trip).

In 1968, Chuck Farnum took an 18-day trip with his son Bill and four of Bill’s high school friends. On the fifth day, Chuck said that they “opted for adventure” and headed from Kawnipi Lake up Devine Creek toward Mack Lake. Bill kept a journal where he wrote, “Up at 8 AM with pancakes for breakfast. Devine Creek divine at first but soon turned into divine crud. Many pullovers, bogs and beaver ponds. Second half stream more difficult. Made our own camp on Fluker Lake at 8 PM, everyone dead tired.” The next day they “bushwacked portage from Fluker to a pothole” and then compassed to Mack Lake which was “a bear of a portage over deadfalls and through muck made more difficult by a high ridge”.

It seems that to the Farnums, a really good trip involves not just heading up a difficult creek, but also crossing at least two long and difficult “portages” over terrain where no portages exist. Even with years of experience in reading maps and using compasses, the Farnums occasionally end up at the top of a cliff with no easy way down, or at a tangled alder swamp with no lake in sight. They have the needed combination of perseverance and experience to not only safely negotiate difficult routes, but to relish them.

A trip to Sawmill Lake, located two miles south of the east end of Pickerel Lake, was one of their more memorable journeys. Chuck Farnham recalls that fascinating trip. “There were just three of us in 1971, my youngest son Bill, his friend Steve, and me. From Rawn Narrows we headed up a long narrow bay northeast toward Howard Lake. The water was deep enough to reach the end of the bay and we found a poorly used portage into the rather unattractive Howard Lake where we camped. What to do now? We noted a small lake on the map named Sawmill, set our compass and set our way eastward. Several hours later we hit the lake on the bottom and came to the fallen remains of an old logging camp, a large brown area about half the size of a football field, completely flat except for the gables jutting up. We explored an old trappers cabin and camped on a peninsula across from the ex camp. It was a hot calm night. Just as we were about to go to sleep, we were submitted to the cacophony of horrendous yowling, yelping, yapping and barking which raised our hair and blood pressure. A shout turned off the noise and we heard the wolves farther away. The noise returned again about 5 A. M. We crawled out of the tent and crept over toward the fallen camp and saw two rather skinny black wolves come out from one of the gables. We broke camp and compassed our way north to the Pines on eastern Pickerel Lake. It was a rewarding experience to see wolves in daylight during the summer. And we finally conquered the Howard route home.”

In order to take these long cross-country portages, the Farnums travel lightly. They eagerly experiment with Kevlar canoes and light-weight camping gear. For many years they have been outfitted by Canoe Canada, and Jim Clark noted that “I love it when they get here and take all of the fancy outfitting apart. They take no plates and no silverware – just eat with a spoon and cup. They take just the essentials”. In 1997 they bushwacked from Alice Lake to Vachon Lake. They then took compass bearings and headed east through the bush to a pothole that is southwest of Buckingham Lake. Chuck’s granddaughter Allison, said that this bushwack was “by far the most challenging portage I have ever experienced. We slept in a swamp, yet Grampy kept his infectious grin”. In the morning, they portaged cross-country to Buckingham Lake and from there they took the established portages back to Pickerel Lake. Ryan Beal, who has accompanied his grandfather on six Quetico trips, wrote that he “has an ability to lead us across a non-existent portage or through rough, stormy waters while claiming that he personally believes such a venture might be foolish. However, we know that at heart he has an insatiable desire for such adventures. He has shown me many things in the woods but most importantly he has shown who he truly is. Through our trips to the Quetico he has revealed what he was like as a youth, as a friend and a father. Over the years there have been many that have been affected greatly by the combination of Chuck Farnum and the Quetico woods, and I am only one. But I do know that I will never take forks, knives, plates, tent stakes or the worries of the outside world into the woods and waters of the Quetico because my Grandfather never did. And I know I that I will always look forward to new adventures in the Quetico and revel in our adventures of the past, thanks to him”.

It isn’t the number of years he’s canoed in Quetico or the number of trips he’s made that make Chuck Farnham extraordinary, it is the youthful enthusiasm that he has somehow maintained and nurtured. He still has a glint in his eye and an urge to explore and see what is around the bend, up the nearest creek or over the next hill. Although he and his travelling companions have ventured farther afield than most, they are well aware that they have only seen a small fraction of what is in Quetico. They have shown that, although we don’t even have to go very far to find adventure, we do have to be far more inventive and adventurous in exploring places where we have previously only canoed the easy and the obvious.